By Natalie Bedouin

Dear Lancaster,

To quote the girl who killed it at the ‘Foreign Soil’-themed Lancaster Story Slam at Tellus 360 last year:

“…it is ok to have more than one place you call home.” Audrey Lopez

Many stories undulated through my blood that night, of moving to a new town, of not having roots here and the implications therein. The questions that loom: how to get by, how to reach the echelon you would like when you don’t already know the land, when you don’t know how those around will receive your presence?

And to Ms. Carrie Hussein, I say thank you, for her story, INVISIBLE AMERICANS, Part 1. I cried tears I needed to cry.

THE IMMIGRANT STORY

The immigrant story, I would like to add, is one we are all mitigating, migrating in different ways all the time. And we all carry travel with us, pilgrimage, survival. I don’t mean ‘survival of the fittest’ survival; I mean the grind, the sweat, the tears, the illusion of the American dream, personified.

As a little girl I was taunted by the kids who were ‘cool’ or ‘home-grown,’ and in high school I left the town I grew up in to start over again in Pennsylvania. What I remember about my public school education in my youth is a few things. The grey area on the map we didn’t talk about, being the place that my parents came from, the exigent need for me to assimilate and the errant idea of multiculturalism which parlayed itself as a form of white hegemonic authority in all of our lives. We didn’t have different as an option, I remember this clearly as my brother too, who is differently-abled, struggled every day to make friends and to fit in.

In New York, I quickly came to recognize, as I noticed in my undergraduate schooling too, that the melting pot is not only a myth, but a complete farce. Yes, we tolerate difference for the most part, but the packs we identify with are ardent and true. In all honesty, as the daughter of two Assyrian Orthodox Christians from the Middle East, the number of Muslim people I know I can still count on one hand. And it was, too, why I was proud to work closely with a Muslim school mate, colleague and friend, Dinu Ahmed, to provide the questions and pedagogy of the work we developed. It was this contention and conflict in community, culture and identity that lead me to create for my thesis project the Racism Dance Theatre Workshop at Bryn Mawr College.

PRESENT

Fast forward ten years, I recently finished reading Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo, by Ntozake Shange— all names that are deeply embedded in earth tones, abilities and presence. This is an ode to the rites of passage of three sisters—coming of age, as a woman, as a person of color, as an artist, as a soul willing to risk itself in love and life. Reminding me that I am not alone in my individual pilgrimage to a foreign city and the torrent of emotional and psychological landscapes there are to traverse.

Soon after reading, I happened to trade this book for a new neighbors’ copy of The Blacker the Berry, by Wallace Thurman. Highlighting how we are inter-related among and beyond our race(s), this way of being with others that can be so harsh and unbound, amidst a culture that is bound by a previous colonial state of servitude now flipped to an incarceration system that suffers a profit at the cost of vice borne out of what I think; Thomas More addresses very well:

“If you suffer your people to be ill-educated, and their manners corrupted from infancy, and then punish them for those crimes to which their first education disposed them, what else is to be concluded, sire, but that you first make thieves and then punish them?”

Ava DuVernay, who directed Selma, is a powerhouse working on a cacophony of life-giving portrayals including The 13th (available now on Netflix), and this past week as I passed a downtown protest ‘supporting law enforcement against violent criminals’ I question this term violent, and I am reminded again of how we cultivate this interaction among diverse populations here in this country. (Ava was on the cover of the September L.A Woman Issue.)

LANCASTER

What Lancaster Transplant embodies that I think few and far between in Lancaster really understand, is that we only grow through bridges built, not on trying to save people and certainly not on and/or by making appearances, or fair weather friendliness.

Moving to a small-town city was a fascinating venture after having lived in a grotesquely large metropolis. Lancaster is, for me, a measured place of grace and forgiveness, you could say. It was where I learned, if you can imagine, how to practice restraint–a very good lesson, in fact.

Lancaster Transplant is a place where people are allowed to be the people ‘they’ know they are at heart. Like my friend Michael at Buzz, reminded me, you must follow your passion.

NOMAD

I think it’s really important to leave the places that you’ve allowed to become familiar. Why? Because (sigh…) often change does not come about without this sort of fresh perspective. You can imagine me now, writ large, getting lost on the somewhat windy and intertwining streets, roads and boulevards of the city of Los Angeles. It is most refreshing, titillating and exacting, a synchronous somewhat haphazard choice to have life on your terms, to practice maintaining your own integrity and still push forward into the things that draw passion from you.

I remember when this Syrian refugee came to the window at Buzz, and he asked me the cost of a coffee, and he decided it was too much and proceeded to discuss with his friend whether they should buy it anyway. He then handed me a $50 bill. His English was poor and I was enraged, and to top it off, he said he was looking for work. “It’s hard to find work here,” he said. I nodded with a confused sense of compassion. I felt my territorial grip tighten, my skin pressing as it stretched further down my shoulders and pooled at the back of my neck. ‘Don’t you see were all lookin’ for work,? We are all trying to get by?’, the American in me snorted, internally.

I was not proud of myself in that moment, to pity another who is not unlike my family, nor unlike myself in a new place trying to make ends meet, looking for a place they can’t really call, but must now call home.

I’ll close with this:

How can we we lift the weight off our shoulders? Every act of kindness, every altruistic movement, every time you shed that kindness upon even yourself is, in sum, adding to the goodness the world is capable of rejuvenating in the face of such depravity.

Natalie Fahima Bedouin

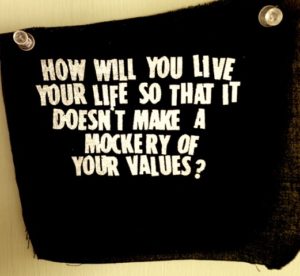

(These images come from an artwork bound camp(ground), I had the privilege to visit in Joshua Tree, CA. this Fall)

Featured image by Al Morrison